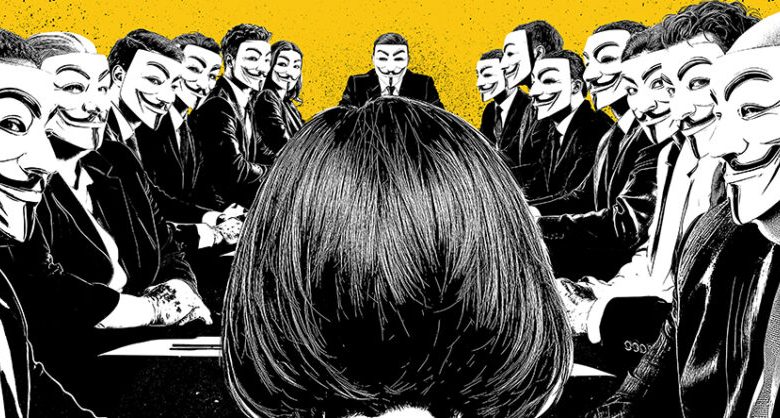

Meet the bond market vigilantes

On the London trading floor of a multinational bank there are rows of desks, each one crowded with monitors. On the walls around the room are large television screens that are constantly on. Half the TVs are set to a financial news channel. The other half show BBC Parliament. This is relatively new; ten years ago, traders would gather to watch a fiscal statement or an election result, and then politics would recede into the background. Now, the focus is permanent.

This has happened for two reasons. Politics has changed, as you’ve probably noticed: we have had six prime ministers in a decade, and already the competition for a seventh has begun. But the market has also changed. When inflation arrived in 2022, it brought an end to the long era of cheap borrowing that had kept the bond markets sedated since 2008. Suddenly, governments were at the mercy of unseen investors, whose bets on the path of inflation and government debt could cause borrowing costs (which reached £111bn in 2025-26) to rise even higher. The bond vigilantes had awoken.

Their first victims were Kwasi Kwarteng and Liz Truss, whose plan for unfunded tax cuts in 2022 caused a market reaction that led government borrowing costs to soar, mortgages to be withdrawn and threatened “widespread financial instability”, according to the Bank of England. After Truss resigned in disgrace, her successor, Rishi Sunak, told an audience – half jokingly – that he wished to thank “my friends, my family and, of course, the UK bond markets”.

The prospect of a repeat Truss Moment is now being invoked in No 10. Labour MPs are being told that any further rebellion against cuts or tax rises will incur the displeasure of the market. When Andrew Marr asked Rachel Reeves this month if she should simply raise income tax and then resign, she replied: “And what do you think would happen in financial markets if I did that?” Reeves’s satisfaction rating is the lowest of any chancellor in half a century of Ipsos polls, but she is still counting on the confidence of hedge funds.

But when the Chancellor goes for meetings in the City, she is rarely introduced to the people whose job it is to press the button on buying or selling several hundred million pounds’ worth of gilts. It is to these people that I have been speaking in the run-up to the Budget. They are well-dressed, intelligent men and women, who like decent restaurants but are mostly unremarkable. You would not guess, while you queue behind them in Pret, that they wield political power, but for them politics is not personal. They approach it with blunt, professional interest, seeing opportunity in chaos. And if Reeves thinks she can rely on their support, she’s wrong.

At a meeting in No 10 in September of this year, one source heard a special adviser ask: “What are gilt yields?” A government whose opponents were destroyed by the bond markets, and which is paying those markets £300m a day in debt interest, apparently employs people who have not taken five minutes to understand how they work.

“Gilts” are UK government bonds, so-called because they were once pieces of paper that were gilt-edged, with gold leaf around the sides. A bond is best understood literally: a bond, a commitment, to pay the person who buys it a given amount of money. This is the best way to borrow money. When we mere punters borrow, we go to a bank and say, “can I have £100”, and the bank says “OK, that will cost you 5 per cent interest each year until you pay it back”. When a government or a large company borrows, it goes to the market and says, “Here is a promise to pay £100 in five years, and I’ll pay the owner 5 per cent interest each year over that time.” Because bonds are sold in an open market, buyers can offer whatever they think they are really worth. They might offer £110 for that £100 bond, meaning the real interest rate, or “yield” paid by the government, will be lower. More importantly, they might offer less than £100 – meaning the yield is higher. This interaction between prices and yields lies at the heart of Britain’s debt dilemma today. When investors judge that a chancellor’s decisions are likely to mean higher inflation or higher borrowing, investors pay less for gilts and yields increase. And so, the state has less money to spend on public services.

On top of this, government bonds, which can have a duration of a few years or a few decades, are not actually held for that long, but are bought and sold repeatedly. The banks that buy them from the government sell them to other investors, who trade them between each other. Trillions of pounds’ worth of government bonds from around the world change hands on a daily basis, changing price as economic conditions shift. This in turn determines how much governments can charge for new debt (or to put it another way, how much it will cost them to borrow).

Now, let’s freshen this up by talking about the only thing more tedious than bonds: pensions. Another core reason why this market in government bonds is more volatile today is that the savings of workers have changed. In decades past, British financial institutions (pension funds and insurance companies) owned most of Britain’s debt on behalf of Britain’s savers. But the “defined benefit” pensions enjoyed by those retirees were not affordable to their employers, and the “defined contribution” schemes that replaced them have a much lower demand for gilts. Around a fifth of UK debt is now owned by pension funds and insurance companies (down from more than 70 per cent in the early 2000s).

At the same time, the amount the government needs to borrow has roughly doubled since 2008, because spending is increasing (on the state pension, among other things) and because our economy isn’t growing to provide the extra cash. Over the same period, the share of our debt owned overseas has almost doubled, to around a third of our national debt. As one investor told me, now is the time of the “marginal buyer” – banks, asset managers and hedge funds, who buy and sell rapidly. “We’re starting to enter the period where the marginal buyer is a lot more picky,” they told me, “and the marginal buyer” – the fabled bond vigilante – “has a lot more power.”

These marginal buyers come in different species. In the City of London, crowded with suits, are the banks (“gilt-edged market makers”, or Gemms) that buy gilts directly from the government, and the asset managers who buy from them. In Mayfair, smaller wealth managers and hedge funds – where the cashmere quarter-zipper is the unspoken uniform – take more speculative positions. Hedge funds, in the UK and abroad, are likely to trade in a riskier, more volatile fashion, using borrowed money to increase the size of their trades (and therefore their gains or losses).

One fund manager who makes trades in gilts that can be worth anywhere from £250m to £1bn described their process to me. The thesis behind the trade – the idea about why particular bonds will make a profit – might be assembled over months or years in advance, and at this stage “it’s all models and economics”. But a good thesis only pays off if it is implemented at the right time. In the few months or weeks before the trade actually happens, “politics plays a huge part”, the fund manager told me. “It dominates the conversation. It’s really, really important.”

After last year’s general election was called, one hedge fund commissioned detailed research on Labour. This is the kind of thing hedge funds do: they buy satellite images of harvests or data on freight movements, looking for information other people don’t have, discovering the true price of something before the rest of the market figures it out. The fund wanted to know who Labour’s MPs and ministers would be, what policies they would have, and how effectively they would deploy them. The polls said Labour was heading for a landslide victory and a huge majority. The research, according to a person familiar with the report, said, “there is no plan, there is no vision, and they’re not going to succeed because they don’t have the talent”. The fund decided to take a short position on UK gilts, effectively betting that Britain’s borrowing costs would rise. They made a lot of money on that bet.

Labour MPs rebellion over the government’s welfare bill in July was further evidence for the market. “When you’ve got a 168 majority and you can’t get through some welfare spending cuts,” one City strategist told me, “the markets have concluded… there’s not a cat in hell’s chance of bringing the fiscal side back.” They pointed to the UK’s £1.4trn in public-sector pensions liabilities and the “explosion in disability benefits for the under thirties” as factors that would prevent investors from buying Britain’s debt. “The bond vigilantes aren’t stupid,” they told me. “They’re looking at this and saying, ‘If your 405 MPs aren’t willing to tackle this… then there’s no hope for you.’”

One investor shared with me the analysis they’d done on the cost of the Labour rebellion. With around 100 Labour MPs prepared to rebel against the government when it attempts fiscal consolidation, they thought it was reasonable to expect that this would add 75 basis points (or three quarters of a percentage point) to the interest on government debt. Over the course of the parliament, they said, this works out to an additional premium on debt of £1bn per rebel MP.

What these rebel MPs fail to understand, the investor said, is that “the role of ministers and chancellors and MPs has changed, because anyone could be speaking to the markets”. There is now a much greater potential for an MP or minister to “say the wrong thing” and incur a market reaction, they told me. “We’ve never been in that scenario before, really, as a country, where that much scrutiny has been placed on people with no training or background… It’s like a child playing with a nuclear reactor.”

The day after the welfare rebellion, the same person watched with their colleagues as Keir Starmer stood at the despatch box for Prime Minister’s Questions and Rachel Reeves, sitting behind him, began to cry. Traders gathered below the TV screens, bewildered at the incompetence that led to the spectacle of the Chancellor in tears before the nation. Since then, the prevailing narrative has been that gilts were sold off as markets worried that Reeves was about to be replaced. Yet this is not, I was told, what really happened. The impulse was not to sell off gilts, but not to trade at all, because they didn’t know why the Chancellor was crying; all they had were rumours. “If you trade in a rumour,” one person explained to me, “that’s market abuse. That’s a conduct issue. You could get fired.” As they refrained from trading, the liquidity – the number of buyers and sellers – in the market fell, and prices became more volatile. The markets were not, in fact, protesting in Reeves’s favour. They were simply holding their breath.

Two months later, Andy Burnham told the New Statesman that he believed Britain should not be “in hock to the bond markets”. Gilt yields rose in response and a Treasury source told the magazine that Burnham’s comments had cost the government £1.5bn in fiscal headroom. But it wasn’t Burnham’s recklessness that caused the markets to stir. It was the fact that a government with the largest majority for 25 years appeared already to be collapsing into infighting.

At the beginning of November, a former Treasury minister was brought in to Downing Street to warn MPs that rebellion around Budget measures could lead to disruption in the bond markets. The Labour MPs I contacted did not seem convinced that the bond vigilantes demand loyalty – one described this argument as “tedious”. No 10 should be concerned by the fact that investors agree.

One fund manager who takes large positions in gilts described the idea that Reeves and Starmer enjoy the protection of the bond vigilantes as “weak”. With each episode that has called the leadership into question, they said – from Reeves’s tears to Burnham’s challenge to recent speculation about a leadership move from Wes Streeting – the market reaction has become progressively more muted. “The market is reacting less and less now to any replacement,” said the fund manager, “because it’s all looking the same.” The vigilantes are becoming less interested in who is holding the wheel, and more interested in whether the wheel is connected to anything.

On Friday 14 November, gilt yields jumped again as reports emerged that Reeves was no longer planning to raise income tax in the Budget. The U-turn was ostensibly prompted by better economic forecasts, but it was the last thing investors wanted to hear. A fund manager told me: “A government that can’t cut spending, can’t tax in a meaningful way, opens up all kinds of unknowns in terms of regarding future revenues and growth… and it leaves extra borrowing to pick up the slack.” That, they said, is “exactly what markets are afraid about”. A strategist at a multinational bank told me one of their assumptions about the UK economy next year was that, “It’s highly likely that [Starmer and Reeves] will both be gone by June.”

Do these people see themselves as having political power, I wondered. Does buying or selling hundreds of millions of pounds in gilts feel like a political act? “Not really,” I was told. “Not as an individual. We’re just doing our best for our investors and clients… but I can see how it looks.”

This is something other politicians seemed to have failed to understand. Liz Truss claimed to have been unseated by an “economic establishment”, while the current government uses the bond vigilantes as spectres to be invoked against anyone who disagrees. Politicians prefer, it seems, to characterise the bond markets as collections of animal spirits rather than office buildings full of self-interested people making long-term predictions about inflation. But politicians also assume – incorrectly – that for these people, market disruption is a bad thing.

In fact, politics has increasingly presented markets with opportunities. Politicians are supplying them with volatility, and a period of volatility, as one source told me, is “when you make tonnes of money”. The chaos caused by the Trump administration’s tariffs on global trade was, they said, their most profitable day for five years. “We take advantage of market chaos.”

Much of the volatility we see in bond markets is out of the government’s hands. Investors choose between the debt of different countries, and the UK bond market is small compared with those of the US and Europe. This means it does not enjoy the same privileges. America’s debt is the currency of global commerce, so the US can run up immense debts – it is in hock to the bond markets, as they say, for $38trn – and people will still queue up to lend it money (for now). France is fiscally profligate, but its position in the eurozone gives it shelter.

Britain is a smaller, less liquid market, and it has to be more careful. As a smaller market we should beware, a strategist told me, “the vigilante bully in the playground”. Investors have to hold a certain amount of someone’s debt – that, fundamentally, is what money is – but the UK, with its dependence on foreign bondholders, cannot afford to take fiscal risks. We do not want to become an example, they said, of what happens “once the markets establish that you are the weakest link”. It is clearly important that Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer try to avoid this from happening, and it may be that they are still the best people to do that. But this does not mean the vigilantes are on their side.

[Further reading: Andy Burnham versus the bond market]

Content from our partners